Cornwall,

a small peninsula at the southwestern tip of England, was considered the home

of the finest hard-rock miners in the world. They mined tin and smelted it with

copper to produce bronze.

The Bronze Age

began about 2150 BC. Bronze is an alloy of tin and copper, two elements prevalent

in Cornwall. The abundance of those metals plus silver brought the Phoenicians,

Greeks and Romans to England. The Romans referred to England as the Tin Islands

and they actively mined there until the 7th century AD. In the Middle Ages,

mining flourished and laws were established solely to protect the interests of Cornwall and Devon miners because of

the importance of the mining industry to the economy of England. This growth

continued until the mid-19th century.

By the mid-1800s, the mines became so

deep that it was no longer economical to continue operations. That, coupled

with foreign competition, sent Cornwall’s

mining industry into a rapid decline. Cornish miners left for other

countries, including the United States. Miners

began leaving as early as the 1850's. America welcomed over a quarter of

a million Cornish immigrants, or some 20 percent of their population, between

1860 and 1900. In the year 1870 alone,

10,000 Cornish miners immigrated.

The

California Gold Rush of 1849 kicked off the era of mining in the American West,

about the time Cornish miners began leaving Cornwall looking for work

elsewhere. In the early days of

underground mining highly skilled Cornish miners with their unusual language

and brogue were imported to do the work. At the time they led the world in

mining technology and were regarded as the greatest hard rock miners in the

world. Their skill with granite and ore won their fame as the elite laborers of

western mining camps. Heirs of a perfected system of excavation, a valuable

terminology, and the technical edge of a culture immersed in sinkings, stopes,

and winzes, they were the world’s best hard-rock miners.

|

| Cornish miners in Dolcoath mine - ctsy John Charles Burrow |

Cornish

miners settled in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Montana, South

Dakota, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California. Many California communities,

such as Grass Valley and Nevada City, hold events to pay tribute to their

heritage of Cornish miners.

|

| Cornish Men's Choir in Grass Valley, California - 1916 |

Many

were attracted to Colorado to help strengthen the state’s mining economy.

Starting in the early days of gold mining in Colorado in places such as Central

City until the first decade of the 1900s, Cornish miners found work and

opportunity in the state with its vast mining sources. It is estimated at sixty

percent of miners who worked in the mines of Georgetown and Silver Plume came

from Cornwall.

|

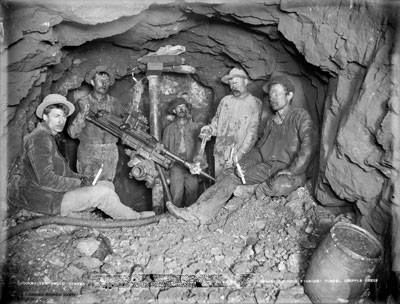

| Cornish miners inside Cripple Creek mine - 1890 (note steam-powered drill) |

Pioneers

in American mining operations, Cornish miners utilized tribute pay to raise

output and made themselves partners with a grueling industry. Expertise made

them company men, superintendents, captains, and drillers, with their success

dependent almost entirely on their own initiative, coolness, and skill. As a

culture the Cornish miners have survived because the nature of their work

itself gave them a resilience and durability that could be transplanted and

take root outside of Cornwall.

When

a foreman was impressed with his Cornish miner, he would ask if there were any

others like him back in Cornwall. The Cornishman usually would know of other

miners wanting to leave the old country and might answer, “My cousin Jack be a

very good miner and ‘ee should like a new job.” The miners reasoned that

foremen would be more apt to accept another member of the miner’s family, where

in fact, the “Cousin Jack” might not be related at all.

Many

came as single men, but they also came in families. This close-knit band of

miners and their wives were known as “Cousin Jacks” and “Cousin Jennies.” The

name is supposed to come from their habit of addressing one another as “cousin”

and Jack was a common Cornish name.

|

| Early flash photography of a Cornish miner drill team |

Although

their skill in working with rock and water was soon recognized, the extremes of

weather and temperature, strange sicknesses, the constant danger of accidents,

and the lawlessness of the camps, all made life hard to endure. Many did not

survive to send home for their families, yet the majority persevered to spread

their legendary mining skills and to bring social as well as religious

stability to mining areas that extended from Wisconsin to California.

Although my latest novel, Nathan's Nurse, does not deal with Cornish miners directly, it was through researching the details to write my scenes within the mines I became familiar with just how prevalent Cornish miners were in the silver mines of Colorado where this novel is set.

Nathan's Nurse is now available. To find the book description and purchase link, please CLICK HERE.

Sources:

https://www.reporterherald.com/2019/11/23/colorado-history-cornish-miners-brought-cousin-jacks-to-colorado/

Wikipedia-Cornish

Americans

https://www.flickr.com/photos/lindyannajones/8044700386

http://www.northvalleymagazine.com/cornish-miners-and-tommyknockers/

https://www.oupress.com/books/9783064/the-cornish-miner-in-america

http://darylburkhard.com/cornishminers.html