Partners, do you want to have some fun today? Yeah? Then come on along with me and a special friend to Sunbonnet Sue's Down Home Radio Roost.

Sunbonnet Sue greets us on her front porch. A rather plump woman of indeterminate age, she's sitting in the shade with a microphone and a tall glass of iced tea, the national drink of Texas.

Sue: "Howdy Lyn. Glad you could drop by. I see you’ve brought a guest."

Lyn: "I’m pleased as punch to be with you today, Sue. This

tall, good looking gent is Jack Lafarge. Um, you might know him as Choctaw

Jack in Dearest Irish. That’s what most people called him until he hooked up with Miss Rose

Devlin."

Sue: "How-do, Mr. Lafarge. I’m right happy to meet you."

Jack smiles and flicks back his long black hair. “Howdy Miz Sue.

It’s nice meeting you, too. Just call me Jack.”

Sue: “My pleasure, Jack. Take a seat and kick back for a

spell. You too, Lyn.” Our hostess points to a pair of rawhide-bottom chairs facing her, and we make ourselves comfortable.

Lyn:

“Jack, why don’t you tell Sue a little about yourself?”

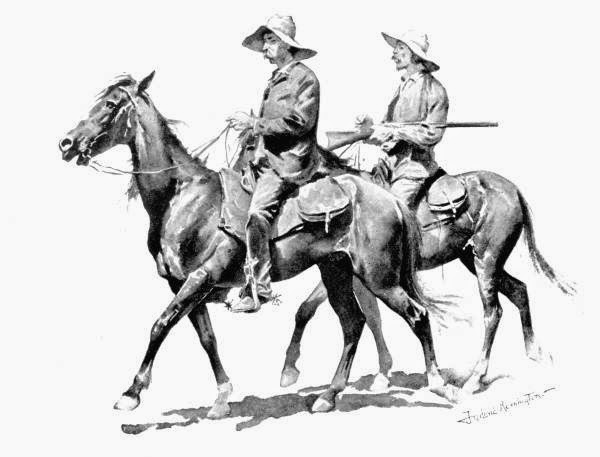

Jack: “Be glad to. I’m a cotton planter’s son, Miz Sue, but

I’ve done some cowboying since the war. Uh, the War of Secession, I mean.”

Sue: “Young fella, I understand you fought on the Confederate

side. Isn’t that a bit odd for a man of Indian blood?”

Jack: “No ma’am. A lot of us from what you white folks call

the Five Civilized Tribes fought on one side or the other. The Choctaws mostly

sided with the South and my pa was half Choctaw. When he joined up, I tagged

along.”

Sue: “You don’t say. As the old saying goes, we learn something new every day. I’ve also heard you’re handy at

blacksmithing. How’d you happen to learn that trade?”

Jack shrugs. “Pa was a blacksmith over in Louisiana

before he moved us to Texas

Sue nods. “I see. So, is your father the person who most

influenced you as you grew up?”

Jack frowns, studying the question. “I’ve never

given that much thought. It’s true Pa influenced me a lot, but so did

my mother. She turned my life around after the war when she convinced me to

walk the white man’s road.”

Lyn: “That’s intriguing, but please don’t go into details.

We don’t want to give away all your secrets. Instead, can you tell Sue about the

scariest moment of your life?”

Jack turns pale beneath his copper coloring. “That

has to be the day my P’ayn-nah, I mean Rose, was bitten by a rattler.” In a

husky voice, he adds, “I nearly lost her.”

Lyn looks guilty. “Oh dear, I’m so sorry for putting the two

of you through that. But the experience did bring you closer

together, didn’t it?”

Jack scowls, ebony eyes glaring at the author. “Yeah, it

did, but that doesn’t mean I forgive you for nearly killing off the woman I

love.”

Lyn squirms uncomfortably. “Yes, well, on a more pleasant

topic, is Rose a good cook? And if so, what’s your favorite food that she fixes?”

Jack’s scowl lifts. Crossing his muscular arms,

he says. “P’ayn-nah – that mean Sugar,

by the way – is a pretty fair cook, even if she burns our supper now and again.

Her favorite food is Indian fry bread, and I reckon it’s mine too. Leastways,

when I get to watch her make it.” He grins, dark eyes twinkling.

Sue laughs. “On that happy note, Jack, I’ll let you head on

back to your Red River home. Thanks for coming

to visit me today. Now, Lyn, why don’t you give me and my

listeners a little taste of Rose and Jack’s exciting story.”

Lyn winks. “I thought you’d never ask, Sue. Here you go.”

Dearest Irish

Texas Devlins, Book Three

Blurb:

Although the story begins in Bosque

County , Texas, where the first two

books in this series both end, much of this paranormal Native American romance

takes place in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma

Rose Devlin, like her older siblings, possesses a rare

psychic power. Rose has the extraordinary ability to heal with her mind, a secret

gift which has caused her great pain in the past. She also keeps another, far

more terrible secret that may prevent her from ever knowing love.

Choctaw Jack, a half-breed cowboy introduced in Dashing Irish, book two of the trilogy,

hides secrets of his own. If they ever come to light, he stands to lose his

job, possibly even his life. Yet, he will risk everything to save someone he

loves, even if it means kidnapping Rose. The greatest risk of all may be to his

heart if he allows himself to care too much for his lovely paleface captive.

Excerpt:

Rose stretched and yawned. Something hard supported her head, and another

something lay half across her face. This object felt like cloth and gave off a

vaguely familiar scent. Swatting whatever it was away, she opened her eyes and

had to squint at the bright sun glaring down at her from on high. In the time

it took to blink and shield her eyes with her hand, everything that had

befallen her during the night burst upon her like a waking nightmare.

Realizing she lay on the hard ground – she had the aches and pains to

prove it – she turned her head to the right and saw Choctaw Jack lying a hand’s

breadth away. He lay on his back, head pillowed on his saddle and one arm

thrown over his eyes. Where was his hat, she wondered absurdly. Recalling the

object she’d pushed off her face, she rose on one elbow and twisted to look

behind her. First, she saw that she’d also been sleeping with a saddle under

her head; then she spotted the hat she’d knocked into the high grass

surrounding them. Jack must have placed it over her face to protect her from

the sun’s burning rays. In view of his threat to beat her if she tried to run

away again, she was surprised by this small kindness.

A throaty snore sounded from her left. Looking in that direction, she saw

Jack’s Indian friend sprawled on his stomach, with his face turned away from

her. He was naked from the waist up, his lower half covered by hide leggings

and what she guessed was a breechcloth, never having seen one before. His long

black hair lay in disarray over his dark copper shoulders.

He snored again, louder this time. Rose’s lips twitched; then she scolded

herself for finding anything remotely amusing in her situation. Glancing

around, she wondered how far they were from the Double C. Jack had been right

to chide her last night. She’d had no idea where they were or in which

direction to run for help. Even more true now, she conceded with a disheartened

sigh.

She heard a horse snuffle. Sitting upright, she craned her neck to see

over the grass and spotted three horses tethered among a stand of nearby trees.

She caught her breath. Was one of them Brownie? Aye, she was certain of it.

Excited and anxious to greet him, she folded aside the blanket cocooning her and

started to rise, but a sharp tug on her ankle made her fall back with an

astonished gasp. Only then did she notice the rope tied loosely around her

ankle. To her dismay, the other end of the rope was wrapped around Jack’s hand.

“Going somewhere?” he asked, startling her.

“You’re awake!” she blurted, meeting his frowning, half-lidded gaze.

“Thanks to you, I am. You didn’t answer my question. Where were you

going?”

“I saw Brownie over there.” She pointed to the trees. “I was only wishing

to let him know I’m here, nothing more.” She swallowed hard, fearing he would

think she’d meant to climb on the stallion and make a run for freedom – though

without a saddle on his back and no one to boost her up¸ ’twould be well nigh

impossible.

Staring at her a moment longer, Jack evidently came to the same

conclusion. “I reckon he’ll be glad to see you,” he said, sitting up and

freeing her ankle. “Go ahead. Say howdy to him.”

She again started to rise, but he forestalled her, saying, “Hold on.

You’d best put your boots back on.” Reaching behind his saddle, he retrieved

her footgear.

“Aye, I suppose there could be cactuses about,” she said tartly,

recalling what he’d said last night. She forced a tight smile.

“Yeah, or snakes.”

Visit Lyn on these sites:

http://lynhorner.com

%2B(320x240)%2B(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)