I became interested in surveyor, William Octavius “Billy” Owen, when I learned that he viewed the 1878 total solar eclipse while on the summit of Medicine Bow Mountain. I started my books that included this particular eclipse with Mail Order Blythe, published in March 2021. I will be publishing Lauren, my fifth and final book with the eclipse connection, in January 2023.

Photographs of Billy Owen are available online, but are part of a protected collection. To see two of those photos, please CLICK HERE.

The parents of Billy Owen were originally from an area near Bristol, England. Before his birth, his father and other extended members of the family joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon). Prior to his birth, his parents and six-month-old sister, Eva, emigrated to the United States. It was in Utah Territory that Billy’s next older sister, Etta, was born in 1856. Billy, the family’s youngest child, was born in 1859. The mother never did join the same church as her husband, and soon decided to leave the Salt Lake Valley and return to England.

Laramie Depot

Billy

Owen never saw a railroad until he was eight years old and the family arrived

in Laramie, Wyoming Territory. Laramie was still a “Hell on Wheels” town, since the

railroad reached

Laramie in early May, five weeks before the Owens did.

It was there his mother learned the inheritance she counted on to pay their passages back to England had disappeared after the death of the family attorney. Going by the name of Sarah Montgomery, Billy’s mother rented some rooms in a hotel on what’s now First Street in Laramie, facing the tracks, and South A. Soon she opened a restaurant and store, just as she had in Idaho. Eva and Etta, by then 15 and 12 years old, helped their mother a great deal.

There were plenty of respectable people in town, but, according to the autobiography Billy wrote when he was sixty-two, there were also plenty of “bar room bums, thugs, garroters, holdups, thieves and murderers from railroad towns to the eastward, and the doings of this mob of criminals form a thrilling page in the history of Laramie.” In that environment, Billy roamed the streets playing pranks with his friends. He roamed the creeks fishing and the prairies hunting with the same friends. They hunted with an antiquated black-powder musket out of which they would shoot gravel and nails when they ran out of bullets.

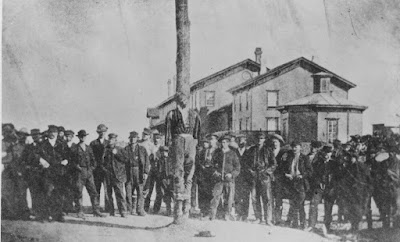

In October, the vigilantes raided the homes of three men — Asa Moore, Con Wagner (or Wager, or Wagan) and Ed “Big Ned” Wilson, shot them full of bullets, and then hanged their bodies from the end of a log building downtown. The same night, they told a number of other toughs to leave town immediately or face the same treatment. Next morning, Billy and his pals got a long look at the bodies. They recognized Moore by his big red flannel neckerchief.

Later the same day, Billy and his friend Phil Bath were in the street when they saw a group of men come out of a saloon, one carrying a coil of rope. In the middle of the bunch was a man known to all as “Long Steve” (aka Steve Young or Steve Long), who had terrorized the town and murdered several citizens. In spite of being warned to leave town, he remained. The vigilantes hanged him on a telegraph pole near the corner of what are now Grand Avenue and First Street, which was by the tracks. A big crowd had gathered, among them Phil and Billy, who watched from 20 feet away. Billy’s sister, Eva, watched from further back in the crowd. After these incidences, Laramie became a safer place to live.

In this picture of the crowd that gathered around the deceased “Long Steve,” the lone boy standing just left of the pole is Billy Owen.

Billy grew up to be a small man, reaching a height of only five feet tall. However, he made up for his size with fierce energy and ambition. He became Wyoming’s best-known surveyor. He loved the work, both the math and the walking.

In the summer of 1878, William O. “Billy” Owen was working with a surveying crew high in the Medicine Bow Mountains, about 36 miles west of Larame Territory. “Over that vast forest,” he later wrote, “the moon’s shadow was advancing with a speed and rush that almost took one’s breath.” This was the total solar eclipse of July 29, 1878.

“It was terrifying, appalling,” Owen’s account continues, “and yet possessed a majestic grandeur and fascination that only one who has seen it can appreciate.”

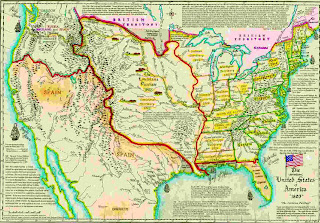

Billy Owen contracted with the precursor to the Federal Bureau of Land Management. From 1881 to 1891, he did over 100 BLM surveys, particularly in the Snake River Valley around Jackson Hole and western Wyoming. He surveyed and established the boundaries of Albany County, and did surveys in every other Wyoming county.

In addition, he held posts as Albany County Surveyor, Laramie City Engineer, and US Examiner of Surveys for the Department of Interior until his retirement in 1914. Active in Republican politics, he was elected Wyoming State Auditor in 1894 and served four years beginning in January 1895. Lake Owen in the Medicine Bow Mountains, which is now a reservoir and part of the City of Cheyenne’s water supply system, is probably named for him.

In 1883, Billy was the first person to ride a bicycle through Yellowstone Park. He and a party of friends were the first people to climb the Grand Teton. Mount Owen, in the Tetons, is named for him.

Billy Owen at the summit of the Grand Teton in August 1924, when he was about 65 years old and made the climb with Paul Petzoldt as guide. The painted steel sign is the same one he and companions left there in 1898. American Heritage Center.

In 1888, Billy married Emma Wilson in Laramie. He and his wife never had children. She weighed 250 pounds and loved to bake him cakes. Billy’s great niece, Alice Downey Nelson, remembered him years later as a smart, fussy man with a short temper and a long, clear memory, who loved to tell stories.

Billy Owen and Emma moved to Los Angeles in 1910. He died in 1947 in Tucson, AZ. A manuscript copy of his 1930s autobiography and Downey family papers (his sister Eva married Stephen W. Downey) are archived at the Laramie Plains Museum.

Lauren is the book in which I actually include the scene involving Billy and the survey crew with which he worked. It is while searching for this survey crew that my hero, Jeb Carter, also views the eclipse.

Lauren is currently on pre-order and will be released January 9, 2023. To find the book description and purchase link, please CLICK HERE.

Sources:

https://www.wyoachs.com/people/2017/12/20/billy-owen-laramie-pioneer-surveyor-and-mountain-climber

https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/kid-hell-wheels-laramie-railroad-arrived

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_O._Owen

https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/kid-hell-wheels-laramie-railroad-arrived