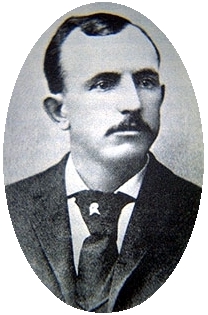

Tom Horn was born in Scotland County, Missouri, in 1860. By his own account, he left home at the age of fourteen. Taking up a series of livestock and stage-driving jobs, he ended up in Arizona Territory. Horn was intelligent and tough. He had an ear for languages and quickly picked up Spanish and later some of the Apache language. He’d also picked up an ability as a tracker.

Therefore, it wasn’t a surprise that while still in his teens he became employed by the Army as a scout and interpreter. The chief of the scouts for the U.S. Army, Al Sieber, recruited Horn in the Army’s campaigns against the Apache. In April 1886, Horn was one of the scouts that escorted the Army column led by Lt. Charles B. Gatewood to find the famed Chiricahua Apache leader, Geronimo.

In his posthumously published autobiography, Horn took credit for the actions of Lt. Gatewood. He claimed it was he whom Geronimo trusted and it was he who convinced Geronimo to surrender. However, the autobiography is the only account of Horn’s involvement with the negotiations.

Whatever the level of his involvement in the surrender of the Chiricahua leader, Horn made a name for himself.The Pinkerton Detective Agency hired Horn, in 1891, to pursue bandits who robbed the Denver and Rio Grande train near Canon City, Colorado. He stayed employed by the Pinkerton’s over the next decade.

About the same time Horn started working for the Pinkerton’s he came to Wyoming. He already had a reputation for certain skills and his services were sought after by some of the prominent ranchers in the area. A few of his “secret” employers included, Ora Haley, John Coble, Coble’s partner Frank Bosler, and the huge Swan Land and Cattle Company.

Yep, folks here we are again with those cattle barons. As discussed in the post on the Johnson County War, the large cattle ranchers were suffering from beef glut and blaming the small ranchers for the lack of grazing land and accusing many of rustling. As many ranchers went out of business and many longstanding cowboys and more recent immigrants to the Territory took up homesteads and other land claims, the once powerful Wyoming Stock Growers Association found its membership and its revenues from dues dwindling drastically.

After the public outcry against the Sweetwater lynchings and the backlash of the Johnson County invasion, the large cattlemen decided to take care of the “rustling problem” in secret. Enter Tom Horn.

By May of 1892, Horn was working for the Pinkertons and was deputized by U.S. Marshal Joseph P. Rankin to investigate a murder in the aftermath of the Johnson County invasion. But by 1895, Horn was most likely fully employed by private interests when he was suspected of murdering two settlers.

The first was William Lewis. Lewis was an English immigrant who moved to Wyoming in 1888. He settled southwest of Iron Mountain between the Chugwater Creek and Ricker Creek on the Laramie-Albany County line. Lewis had been jailed for stealing clothing and cheating a boy at a faro game. He was suspected of cattle theft and under a court order to refrain from butchering cattle.

In July 1895, Lewis received a letter telling him to leave the area. He ignored the warning, and on July 31st, as Lewis was loading skinned beef into a wagon he was shot three times. The coroner estimated the shooting had been done from a distance of 300 yards. A rumor circulated about an offer Tom Horn made at the Stockgrowers’ Association and the tall stock detective, Tom Horn, was summoned for questioning.

Horn was located in the Bates Hole region of Natrona County, two counties away. Laramie County Prosecutor, John C. Baird assumed Horn was hiding out after the shooting and prepared an indictment. However, Tom Horn had a number of rancher and cowboy witnesses who were willing to swear straight faced that he had been in Bates Hole the day of the killing. The alibi couldn’t be shaken and the authorities released him.

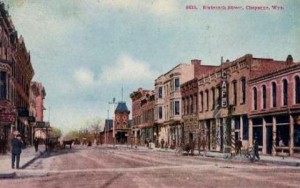

Horn immediately rode into Cheyenne and indulged in a ten-day drinking spree dropping hints at the truth. “Dead center at three hundred yards, that coroner said!” And he grinned. “Three shots in that fella ‘fore he hit the ground. You reckon there’s two men in this state can shoot like that.” Publicly, he denied everything. Privately, he created a blood-chilling image of himself as a hired assassin.

The second settler was, Fred Powell. Powell homesteaded with his wife Mary and 18 month old son Billy east of Laramie County. The marriage was not a blissful one, and Fred carried a long scar on his face where Mary took a butcher knife to him. Powell was charged with stealing cattle and horses at least seven times, each time he was let go for lack of evidence. Evicted from his homestead he moved to another along Horse Creek, proving up his claim in 1892. Like Lewis, Fred started receiving notes telling him to get out. Powell ignored the warnings.

On the morning of September 10, 1895, Powell and his hired hand Andy Ross were along the creek working when Ross saw Powell clutch his chest and gasp, “My God, I’m shot!” He collapsed and died.

Again, Tom Horn was the first suspect, and was brought in for questioning. Horn shook his head and kept his face expressionless and his voice calm. He had a strongly supported alibi ready, and again he was released.

Enjoying a night of liquor and entertainment provided by the professional ladies of Cheyenne, Horn made vague insinuations admitting to the killings. “Exterminatin’ cow thieves is just a business proposition with me. And I sort of got a corner on the market.”

After a friend once told him that he didn’t think dry-gulchin’ a man seemed very sporting. Horn replied in amazement, "I seen a lot o' things in my time. I found a trooper once the Apache had spread-eagled on an ant hill, and another time we ran across some teamsters they'd caught, tied upside down on their own wagon wheels over little fires until their brains was exploded right out o' their skulls. I heard o' Texas cattlemen wrappin' a cow thief up in green hides and lettin' the sun shrink 'em and squeeze him to death. But there 's one thing I never seen or heard of, one thing I just don't think there is, and that's a sportin' way o' killin' a man."

After the first two murders, the warning notes were rarely ignored. The lesson learned.

When Fred Powell's brother-in-law, Charlie Keane, moved into the dead man's home, the anonymous letter writer took no chances on Charlie taking up where Fred had left off and wasted no time on a first notice: "IF YOU DON'T LEAVE THIS COUNTRY WITHIN 3 DAYS, YOUR LIFE WILL BE TAKEN THE SAME AS POWELL'S WAS." This was the message found tacked to the cabin door. Keane left, within three days.

For three straight years, Tom Horn patrolled the southern Wyoming pastures. How many men he killed after Lewis and Powell, if he killed Lewis and Powell will never be known.

One of Horn’s most notable “clients” was Wyoming Governor W.A. Richards who was being plagued by cattle theft on his own land. Richards was good friends with W.C. “Billy” Irvine president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. In a meeting between the two men, Richards told Irvine he would like to meet Tom Horn, but didn’t want him coming to the Governor’s office. Irvine offered to hold the meeting in the WSGA President’s office just down the hall. Horn, in his usual calm manner, informed the Governor he would either drive every rustler out of Big Horn County, or take no pay. But when he finished the job to the governor’s satisfaction he would receive $5000.00. Horn put no limit on the number of men he planned to kill. Though stunned, Richards agreed. After Horn left Richards told Irvine, “So that is Tom Horn! A very different man from what I expected to meet. Why, he is not bad-looking, and is quite intelligent; but a cool devil, ain’t he?”

Horn continued his work as a cattle detective through the 1890s. In 1900, he murdered Matt Rash and Isom Dart, two suspected cattle thieves, in Brown’s Park where the Colorado, Utah and Wyoming borders intersect. The crimes received little notice in Wyoming.

The only thing cattlemen hated more than homesteaders were sheepherders. And while the large and small cattlemen fought amongst themselves the sheepherder entered the territory taking over land and grazing their destructive herds over the already crowded land. But it didn’t take long for the eyes of the cattleman to turn his wrath on the sheepherder. We’ll get into all this in more detail next week, but for now we’re looking at one particular sheepherder Kels Nickell.

Seven miles from Iron Mountain was the ranch of Kels Nickell, the only sheepherder in the area. On July 18, 1901, Nickell’s fourteen-year-old son, Willie was shot and killed by two bullets to the back. Willie, tall for his age, wore his father’s coat and hat and rode his father’s favorite horse, and therefore it was believed the killer mistook him for Kels. Though Willie fell face down, someone turned the body over and placed a stone under Willie’s head. There were no footprints or shells left at the scene. Seventeen days after that, Kels was shot, wounding him in the arm, hip and side. While he was in the hospital, masked men clubbed a number of Kels’ sheep to death. The Nickell family moved to Saratoga not long after he recovered.

Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors was hired by the county commissioners in Cheyenne to investigate the crime. LeFors used letters from a former boss in Miles City, Montana stating the need for someone to do a “secret” job to lure Tom Horn out of hiding.

Horn left John Coble’s place in Bosler meeting LeFors at the U.S. Marshal’s office in Cheyenne on January 11, 1902. LeFors secreted a stenographer, Charles Olnhaus, and a witness, Laramie County Deputy Sheriff Leslie Snow, behind a locked door. Over the course of a two hour interview, LeFors led Horn into making a series of incriminating remarks about the Nickell killing. The most damaging statement being, “It was the best shot I ever mad and the dirtiest trick I ever done.”

Horn allegedly told LeFors that he had been paid in advance and received $2,100 for killing three men and taking five shots at another. He told LeFors the reason there were no footprints is he was barefoot. LeFors asked whether Horn had carried the shells away, to which Horn responded: "You bet your [expletive deleted] life I did." On Monday, January 13, Laramie County Sheriff Edwin J. Smalley, accompanied by Deputy Sheriff Richard A. Proctor and Cheyenne Chief of Police Sandy McNeil arrested Tom Horn in the bar of the Inter-Ocean Hotel. Deputy United States Marshal Joe LeFors watched.

John Coble paid for Horn’s defense, with the general counsel for the Union Pacific, John W. Lacey representing Horn. The trial was held during an election year with both Prosecutor Walter R. Stoll and Judge Richard Scott up for re-election. On top of this, public interest in the case was overwhelming and the trial received widespread newspaper coverage in Wyoming and Colorado.

Horn’s defense was three-fold:

(1.) Horn was under the influence of liquor, tended to make things up, and became talkative when drunk. Witnesses were produced that Horn had been drinking. He denied making the statements in the Scandinavian. He contended that his jaw had already been broken when he was in the Scandinavian and with the cast he could not talk.

(2.) Horn had an alibi and could not have been in the Nickell ranch at the time of the killing. He was in Laramie City, as proven by the fact that Horn's horse, Pacer, was lodged at the Elkhorn Livery in Laramie City for a ten-day period at the time of the killing. Witnesses testified that Horn was nowhere near the Nickell Ranch at the time of the slaying.

(3.) The killing could not have occurred as he described to LeFors in the following regards: (a.) Dr. Amos Barber testified, based on learned texts, that the wounds could not have been inflicted with a 30-30 similar to Horn's. (b.) Frank Stone had bunked with Horn several days later and had observed no injury to Horn's feet such as would have been produced had Horn gone barefoot. One of Horn's lawyers testified to having examined the area of the Nickell gate where the killing took place. He testified that the area was strewn with cacti and rocks such that no one could go barefoot in the area. Samples of the rocks were introduced into evidence. (c.) Horn, in his statement to LeFors, described the shooting as coming from one direction. The fatal shot came from another.

Horn took the stand in his own defense. The cross-examination by the prosecutor, Walter Stoll, was devastating. Statement by statement, Horn admitted making the various statements testified to by LeFors, Snow and Ohnhaus with the exception of one statement which Horn did not remember but conceded he might have made.

Horn’s lawyer closed emphasizing all evidence was circumstantial, and Horn’s supposed confession was nothing but drunken boasting.

The prosecution claimed Horn killed Willie Nickell to keep the boy from reporting his presence in the area. But in the day before sequestered juries it is likely they had their minds made up before they entered the courtroom.

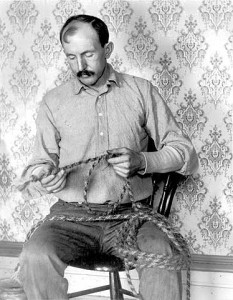

Despite appeals to the Governor to spare Horn and fears that Horns numerous friends would attempt a jail break, on November 20, 1903, Horn was hanged at the Cheyenne jail. Prior to his hanging, Horn spent his time in jail braiding a rope. When it was clear his time was at an end, Horn wrote John Coble:

Dear Johnnie:

Proctor told me that it was all over with me except

the applause part of the game.

You know they can't hurt a Christian, and as I am

prepared, it is all right.

I throuroughly appreceiate all you have done for me.

No one could have done more. Kindly accept my thanks,

for if ever a man had a true friend, you have proven your-

self one to me.

Remember me kindly to all my friends, if I have any

besides yourself.

Tom Horn remains a controversial character due to the lingering questions regarding his guilt or innocence in the Nickell murder. There's also a question regarding the WSGA's involvement with the trial, and the contention Horn was a scapegoat for the powerful cattlemen. Horn’s supporters and later historians questioned his confession to LeFors stating LeFors got Horn drunk and tricked him. Others stand firm that not only did Horn kill Willie Nickell, but an unknown number of men, and that Horn received a fair trial and was represented by one of the finest trial attorneys in Wyoming.

Like the outcome of the Johnson County War, more than the question of Horn’s guilt or innocence is the political shift evident in Wyoming during his trial. Horn, friend of cattle barons was convicted and executed. Their power once unquestionable was on the dwindle as ordinary Wyoming citizens refused to cower under their heavy hand.

SOURCES:

Carlson, Chip. Tom Horn: Blood on the Moon : Dark History of the Murderous Cattle Detective, High Plains Pr., Sept 2001.

Ball, Larry D. Tom Horn in Life and Legend. University of Oklahoma Press., 2014.

http://www.wyohistory.org/essays/tom-horn

http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/horn.html

Kirsten Lynn writes stories based on the people and history of the West, more specifically those who live and love in Wyoming and Montana. Using her MA in Naval History, Kirsten, weaves her love of the West and the military together in many of her stories, merging these two halves of her heart. When she's not roping, riding and rabble-rousing with the cowboys and cowgirls who reside in her endless imagination, Kirsten works as a professional historian.

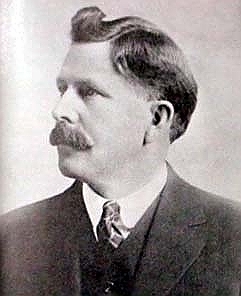

I just knew he was a fascinating figure in history. Funny, he doesn't look like a cold-blooded killer--he's handsome and clean and smart. Well, probably too smart, as it sounds likely he did have a big hand in all these killings.

ReplyDeleteEven a cold-blooded killer--why would one kill a young boy?

Thanks, Kirsten, for telling us all about Tom Horn. The photos are great, too.

Glad you enjoyed the post, Celia. Yes, that's part of the reason Tom's execution was so controversial is many people liked him, and he was intelligent and had a quick wit. Unfortunately, he also had a big mouth that he shot off when he should keep his lips sealed.

ReplyDeleteI don't think anyone understands why he killed the young Nickells boy. Some still argue he thought it was the father Kels. I guess it's one of those things where only the grave knows the whole tale.

Excellent post, Kirsten. Scary to think there were men who were personable, but deadly.

ReplyDeleteThanks so much, Caroline.

ReplyDeleteIt is scary, but if you think about it some of this century's serial killers were personable, as well.

That was an excellent read. I enjoyed it very much. Thank you!

ReplyDelete