By

Caroline Clemmons

Suppose

you were hiking and became lost. Or, perhaps you’ve been kidnapped and are

escaping from your captors. Suppose you’re a pioneer whose horse is startled

and throws you, then takes off with your provisions. What would you do?

This

question puzzled me several years ago when I wrote a book in which the heroine

rushed through a snowstorm to rescue her stepson (Surprise Brides: Jamie).

They’re lost, but know the hero will come for them. Until then, what can she do

to protect and feed them?

When I

was a small child, our neighbor in Bakersfield, California, harvested wild

foods such as mushrooms, prickly pear cactus pads and flowers, and dandelions.

There were more, but small kids don’t notice everything. My mom—also known as

the pickiest eater ever—thought her friend was going to poison herself and her

family. Yet, the family thrived. But, that memory wouldn’t help me with the

book set in snow by a forest.

Even in winter, edible plants are available. But beware! There are also poisonous plants (as I used in Brazos Bride and High Stakes Bride in the Stone Mountain TX series). How do you tell the difference?

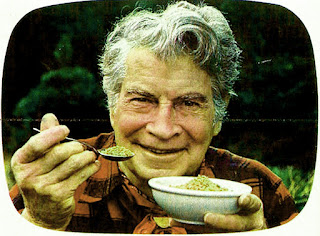

After entering the University of Hawaii as a 36-year-old

freshman, Gibbons majored in anthropology and won the university's

creative-writing prize. In 1948, he married Freda Fryer, a teacher, and both

joined the Society of Friends (the Quakers). The couple relocated to the

mainland in 1953, where Gibbons became a staff member at Pendle Hill Quaker

Study Center near Philadelphia. While there, he cooked breakfast for everyone

every day. Around 1960, through his wife's urging and support, he was able to

follow through on his earlier aspirations and turn to writing.

Capitalizing on the growing return-to-nature movement in 1962,

the resulting work, Stalking the Wild Asparagus, became an instant

success. Gibbons then produced the cookbooks Stalking the Blue-Eyed Scallop in

1964 and Stalking the Healthful Herbs in 1966. He was widely published

in various magazines, including two pieces that appeared in National

Geographic.

The first article, in the July 1972 issue, described a two-week

stay on an uninhabited island off the coast of Maine. Gibbons, along with his

wife Freda and a few family friends, relied solely on the island's resources

for sustenance. The second article, which appeared in the August 1973 issue,

features Gibbons, along with granddaughter Colleen, grandson Mike, and

daughter-in-law Patricia, stalking wild foods in four western states.

Gibbons was not a survivalist, but simply an

advocate of nutritious but neglected plants. He typically prepared these in the

kitchen with abundant use of spices, butter, and garnishes. Several of his

books discuss what he called "wild parties", dinner parties where

guests were served dishes prepared from plants gathered in the wild. His

favorite recommendations included lamb’s quarters, rose hips, young dandelion

shoots, stinging nettle, and cattails. He often pointed out that gardeners

threw away the more tasty and healthy crop when they pulled such weeds as

purslane and amaranth out from among their spinach

plants.

His death occurred December 29, 1975 in Pennsylvania.

A rumor spread that Gibbons died from eating a bad mushroom. That is not true.

He die of an inherited disease called Marfan syndrome, which caused a ruptured

aortic aneurysm.

But that doesn’t help us survive in a Colorado

winter.

Cattail–. I checked many sources and learned that every part

of the cattail was used by Native Americans. My heroine dug up the bulbous

roots and baked them like potatoes. In

late winter the first shoots that are starting to emerge are reported to taste

good.

Conifer Needles– The needles of evergreen conifers are probably the easiest and most

widespread thing to forage in winter, even in the coldest climates. Most

conifers are edible, with the exception of the yew tree, which is toxic.

According to several sources, pine, spruce, fir, and redwood needles make a “tasty”

tea.

Juniper Berries– aren’t really berries at all. They are actually a fleshy

pine cone with a distinctive scent and flavor. They are most commonly used as a

spice rather than a food, and they are the main flavoring agent for gin. A

well-known Aspen restauranteur uses them as a spice and as a garnish.

Birch Bark and Branches–Birch trees are another one that can be

foraged in colder regions. The bark and small twigs and branches can be made

into a tea. The inner bark can also be made into a flour substitute. (Don’t take too much of the

bark from one tree as it can be harmful to the growth of the tree.)

Tree

Sap– Beyond maples, many trees can be tapped for sap, even black walnut. This is something that is usually done

towards the end of winter, as temperatures are just barely starting to get

warmer, but the exact timing is dependent on your location. Birch trees are tapped earlier than most, often in late winter, and you

can even ferment the birch sap into wine.

Acorns– The nuts of oak trees, acorns (along with most other nuts) come into

season in the fall, but you may still be able to find some in the winter if the

squirrels haven’t gotten to them first. Acorns require processing first to make them

edible, but the resulting flour is supposedly good enough to be used for flatbread. I heard a Native American lecture on the process, and

if you were stranded, you might starve before you finished the process.

Maple Tree Seeds– The little helicopter seeds from maples are edible.

They may be a bit dried up and may not taste great in winter, but they are

often still hanging around.

Dock Seeds–Curly dock and yellow

dock are common leafy weeds that are foraged in spring and summer for their

greens. In late summer they shoot up a large stalk that will eventually be

covered in seeds in fall. Once winter comes, the plant will die back, leaving

the dried seed stalk. I’ve heard it’s a pain to forage dock seeds and do much with them, but

they can be made into a flour.

Rose Hips–Rose hips are the fruit of the rose flower, and can be found in the

wild or in cultivation. They appear in the fall, but may persist through most

of the winter, often covered in snow or ice. They are high in vitamin C, and

good for tea, jelly, or rose hip syrup. Supposedly, the cold makes them sweeter but a little mushy.

Hawthorn Berries– There are many types of hawthorn berries, and

they also persist into wintertime. Not all varieties taste great, but none are

poisonous, except for the seeds. Don’t eat the seeds! The berries are high in pectin

and can be used to make jelly or jam.

Wintergreen (Teaberry or

Checkerberry)–Teaberries, also called checkerberries, are

the berries of the wintergreen plant. They will over winter and will often

still be on the plant when the snow melts in the spring. The leaves of

wintergreen are also edible and can be chewed on or made into a tea.

Uva Ursi (Bearberry or Kinnikinnick)– Uva Ursi is common in the Western states, and is highly prized for its medicinal properties, particularly for urinary

tract infections. It does produce berries, but they aren’t tasty, so is more

commonly used for its leaves. It’s a low growing relative to the manzanita, and looks somewhat similar. In

winter it can be found under the snow, if you are willing to dig for it.

Watercress– This water plant loves cold water and will often grow all

winter long. Watercress is a peppery

tasting green that is used in salads or any other way that you would use leafy

greens.

Oregon Grape– While there probably won’t be any berries left on Oregon grape plants in the winter, the inner

bark of the stems and roots is highly medicinal. It contains berberine, the

same compound that’s in goldenseal, which is beneficial for the immune system,

as well as being antibacterial and anti-inflammatory. Note that Oregon grape

is at risk for being over-harvested and is on the plants to watch list.

Burdock Burdock is a thistle

that has an edible root. In fact, there are many types of thistles that

have edible roots that you might be able to dig up, as long as the ground isn’t

totally frozen solid.

Chicory–Chicory grows almost everywhere and the

root can be harvested all through the winter (once again, if your ground isn’t

completely frozen solid). It makes a nice coffee substitute if you’re in need

of a hot drink.

Dandelion–Dandelion root can also be collected through the winter if the ground isn’t too frozen. One author (Wild Food Girl) wrote:

“Other recent snow-forage we’ve found in the Colorado high country includes dandelions, currants, and gooseberries. We found the dandelion greens poking out of snow from grassy beds under willows along the same mining road. Some were as long as my arm!

I took a small

bag and they almost wilted by the time I got home so I washed and ran them

through the food processor immediately. The chopped greens smell exactly like a

fresh mowed lawn—which, instead of off-putting, is a smell we treasure, as we

don’t get much of it in these parts. To this I added finely chopped raw onions,

oil, soy sauce, and tofu cubes for a batch of the cold marinated salad that has

become my go-to dandelion recipe. Yum!"

Many edible mushrooms can be foraged during the winter,

especially those that grow on trees above the snowline. .

Yellowfoot Chantrelles– Also called winter chanterelles these tasty mushrooms in

the chanterelle family can be found through most

of the winter. They have the same false gills as chanterelles, but a hollow

stem.

Oyster Mushrooms–Oyster mushrooms grow on downed logs or

standing dead wood, and can often be found year round. They won’t tolerate a

hard freeze.

Chaga Fungus–Chaga fungus is all the rage right now with its powerful

medicinal properties. It presents as a large knobby growth, usually on birch trees. Great care is required when

harvesting to ensure that it will come back year after year, as it is a very

slow grower.

Turkey Tail Mushroom– This medicinal mushroom also grows on trees through

the winter, making it great to forage in the colder months. Turkey tail mushrooms are

usually made into a tincture. They support the immune system.

Now you know how to survive in the

wilds of winter. Have fun foraging. As for me, I find writing about adventures far more appealing than

having them. I’ll be waiting at home.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euell_Gibbons

https://www.growforagecookferment.com/what-to-forage-in-winter/

https://wildfoodgirl.com/2011/theres-no-foraging-like-snow-foraging/

http://www.coloradoplants.org/edible.php

How interesting. I used to live in the country, but was afraid if I foraged I would pick a poisonous plant instead of an edible one. I do my foraging at the grocery store.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Caroline for your extensive research about edible foods found in the forests, especially in wintertime. Rather timely, since I may have my main character in my WIP lost in the Colorado mountains.

ReplyDelete