Despite incredible hardships at the beginning of the 3,000 mile journey, diarist Celinda Hines was quietly optimistic. She recorded how many miles they covered each day, opening each diary entry with a few sentences praising the scenery. She didn’t understate or ignore the hardships that belonged to that lovely scenery. She also noted how many graves or markers they'd seen that day, and mentioned when the grave was opened and the results.

One grave belonged to a young woman; her bones and clothes were strewn all around the grave. It was dug open by wolves. She also mentions, briefly, though sometimes in individual sections, about the high number of wolves and how they behaved. She dreaded going out of doors alone after dark because of the hungry, howling circling wolves; indeed, she didn't do it.

Most of her daily entries for weeks centered around the six or more ravines they’d crossed in the morning, then six more in the afternoon, whether they were on the plains or among rolling hills. Some ravines meant building bridges; most meant skillfully getting taking themselves and their livestock over them. She also mentioned the few times they lost animals. She was more tolerant of river crossings, where all their stock successfully swam from one side to the other. She was also fairly cheerful - at least she wasn't angry - about accidents.

The family was forced by heavy rains one night to all sleep in one wagon, but before dawn, the bedding and their clothes were soaked through. The road tipped the wagon over, crushing the diarist under household goods until she too was tipped into the mud. None of these entries was more than four or five sentences in length; and praising the weather and scenery accounted for two.

It

was interesting that none of these women, even when left alone while the men

located missing livestock, were accosted by burglars or Indians. They mentioned which Indian territory they’d

entered (such as Pawnee), and sometimes told of a visit from an Indian they knew; but they had no trouble

– as they said, of any scope.

An Indian friend of a friend told them to take a route different from the one pioneers usually used; he said the road was much better. Celinda did not once refer to this as treachery or degradation (common terms of the time toward Indians), though she mentioned that the road was terrible. She never said his name or which tribe; she continued her daily reports about the condition of the road, and it was 'good' only once or twice. I have to decide that she learned from her errors, but decided not to dwell on them.

Another

reason for optimism is the California gold rush of the 1850’s – many of these wagon pioneers were part of that ‘fever.’ They were thrilled to be starting over, taking their savings and money from selling everything they'd owned back East. Individual men joined together and went with one group of pioneers, and left and went with a different group if they felt they'd travel faster. Many wagon groups didn't travel on the Sabbath.

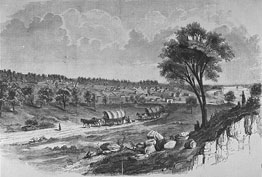

"Jumping-off towns" or starting-off places like St. Joseph, Missouri, or Independence or Council Bluffs, where people were outfitted for the gold rush (or mining, or farming) were often thriving, populous towns. St. Joseph burst from a couple of shops to 3,000 permanent citizens and 10,000 transients living in tents, waiting to 'jump.'

Independence, Missouri 1855

At other times, though, a town of women left alone was dangerous. When raids occurred, as they frequently did in 'Bleeding Kansas,' it was disastrous. The leaders of Kansas Territory demanded that all able-bodied men leave their towns to protect the border with Missouri. (Kansas Territory was trying to establish itself as a free state; Missouri was Pro-Slavery, and the third group, the Abolitionists led by John Brown, also stirred things up, and violence routinely occurred. The US Parks service refers to 'Bleeding Kansas': 'During Bleeding Kansas, murder, mayhem, destruction and psychological warfare became a code of conduct in Eastern Kansas and Western Missouri.' One diarist wrote that the towns after raids looked worse than those of the Civil War after burning and looting. She gave no particulars.)

People didn't realize, she wrote, how violent Kansas and Missouri had become until they'd stopped off there. To pioneers from the eastern parts, these areas were simply en route to the far West. Sometimes they settled there only to learn that their sentiments back home were suspect; sometimes they were appreciated, but still raised suspicion.

If a person came from a slave-owning or southern state, while they were traveling they were mocked for their speech, their accents, the food they ate, and asked outright if they'd brought their slaves with them. (She wrote that any answer would be dangerous.) The reverse was true for non-slave area pioneers. If the pioneers happened to ignore all these jeers and started to establish themselves in a contrary area, they found themselves in danger. Sometimes they changed people's initial reactions by doing as the residents did, like joining groups and doing charitable works the group sponsored. This pressure somewhat eased when Kansas became a state. One woman wrote that by the time Kansas was recognized, it was the poorest, most ragged-clothed member of the Union.

Helpful Pioneer Woman Making Soap

How interesting to have first hand accounts of crossing the plains. I'm surprised she didn't refer more often to the danger. Surely it was on her mind. Perhaps she only addressed what she could control. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteVery good information, Cora. Thank you for sharing your meticulous research with us. It's always fascinating to delve into the particulars of historical events and learn new things.

ReplyDelete