The first known envelope was nothing like the paper envelope we know of today. It can be dated back to around 3500 to 3200 BC in the ancient Middle East. Hollow, clay spheres were molded around financial tokens and used in private transactions. The two people who discovered these first envelopes were Jacques de Morgan (1901) and Roland de Mecquenem (1907).

Paper envelopes were developed in China, where paper was invented by 2nd century BC. They were used to store gifts of money.

Letter Sheet

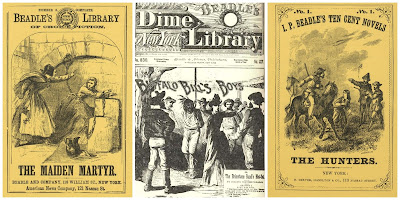

Prior to 1845, hand-made envelopes were all that were available for use, both commercial and domestic. Since most people could not read or write, very few had a use for letter paper or envelopes. Envelopes were generally handmade and mainly used by the well-to-do who could afford to send private letters and invitations to social gatherings.

In the early 1800s, the cost of a letter depended on how many sheets of paper were included. An envelope was charged as an extra piece of paper. Most ordinary people folded and sealed the letter so the address could be written on the blank back. Some used intricate folding; other used wax to seal the flap or the edges. Hot wax, made from bees’ wax and resin, would be dripped on to the edges to be sealed and stamped with the motif of the sender.

|

| Rowland Hill |

In 1837, social reformer Sir Rowland Hill published the document, “Post Office Reform”, which revealed how a stamp with a gum backing and a pre-paid penny wrapper were to be created. Local businesses created them through the lengthy process of cutting and hand-folding an envelope template. However, demand was growing quickly due to the universal postage system and companies manufacturing hand folded envelopes simply couldn’t keep up.

Classic envelope design made from Diamond-shaped sheet

In 1845, Edwin Hill and Warren De La Rue were granted a British patent for the first envelope-making machine. Their first envelopes shaped like flat diamonds or rhombus-shaped sheets called blanks that were pre-cut before being fed into a machine which creased them to create a rectangular enclosure. The edges of the overlapping flaps treated with a paste or other adhesive. It was up to the sender to secure the open flap. Generally, the flap could be held together with a wax seal on the point.

U.S. postal reform in the 1840s changed how both businesses and individuals used the mails. Postage was no longer calculated by the number of sheets a letter contained. Instead, the cost was based upon weight and distance. By 1851, a one-ounce letter could be sent across the nation for as low as three cents. Lower rates encouraged more Americans to use mail on a regular basis.

1879 U.S. Stamped Envelope

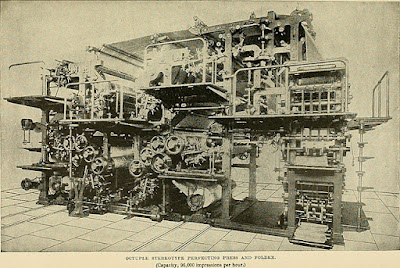

Envelope-making machine

Hawes, who was a Massachusetts physician, invented an envelope-making machine and was granted a patent in the United States in 1853. He left his practice to work for paper machinery manufacturer Goddard, Rice & Company. Building on earlier designs, he added a self-feeder that automatically picked up the blanks. This reduced the manpower required by earlier machines, increased the speed of production, and provided the basis for the principles that would be used in later years to develop self-gumming plunger machines. Hawes’s machines turned out an impressive 10,000 to 12,500 envelopes per day.

1883 Pimpton Fawn Envelope

Throughout the mid to late 19th century, many inventors and manufacturers developed envelope machines that improved upon the processes of folding, gumming, and drying. In 1862 or early 1863, inventor George H. Reay who worked for Berlin and Jones, a leading envelope manufacturing company in New York, developed a reliable folding machine that became an industry standard of the time. Then, in the late 1860s, Thomas Waymouth, another inventor with Berlin and Jones, developed a self-gumming and folding machine that proved to be a huge advance in the industry.

1893 PostmarkWhile Waymouth’s machine further progressed envelope manufacturing, it also made it harder for other inventors to take the self-gumming concept further. It was difficult to invent a new machine that did not infringe on Waymouth’s patent. In 1871, two inventor brothers, Henry D. and Daniel W. Swift who created numerous envelope-manufacturing machines while working for G. Henry Whitcomb & Co. in Worcester, MA, developed a gummed envelope machine. Their process had the ability of gumming envelopes without worker assistance. This major breakthrough in the process would lead to future generations mass-producing envelopes more efficiently.

The years following the American Civil War saw an increase of correspondence between those who remained in the East, and those who traveled to the West. This was particularly true for those men―primarily in the West―and women―primarily in the East―who used correspondence as a means of seeking suitable marriage partners.

My upcoming Christmas romance is set in 1878, several years after gummed envelope machines were available and creating covers for sending letters. Figgy Pudding by Francine is currently on pre-order and will be available for release on 11/22/21. To read the book description and find the link, please CLICK HERE.

Sources:

Wikimedia Commons

https://www.envelopes.com/blog/the-history-of-envelopes/

https://www.cavaliermailing.com/the-history-of-envelopes/

Wikipedia