I’m so good at doing things backwards. I recently published a book about train travel in which I highlighted some of the employees on the train due to arrive in 1881. I thought I researched the railroad fairly well. I got it mostly right, but not quite. In my story, I have about three conductors. In reality, there is only one conductor on a train, although he might have assistants. All is not lost, though. I have a couple of book plots coming up that involve train travel. My new-found knowledge will come in handy.

Here are a few jobs that helped a nineteenth century train run smoothly.

Engineer

The engineer was responsible for operating the locomotive. He was also in charge of the mechanical operation of the train, train speed, and all train handling. If the locomotive needed to be repaired in a remote area, he was the one who fixed it. He is responsible for preparing equipment for service, checking paperwork and the condition of his locomotive. He is also in charge of the mechanical operation of the train including controlling steam pressure, boiler water level, fire box temperature, acceleration, braking, and handling of the train underway. He needs to know the physical characteristics of the railroad, including passenger stations, the incline and decline of the right-of-way and speed limits. As the train is moving he watches for obstructions on the rails ahead.

Since he was able to make the steam engine come to life and pull the train, the locomotive Engineer was the most heroic and glamorous train figure during the nineteenth century. He enjoyed certain privileges of the position. He was allowed to have his engine painted whatever colors he chose. He was allowed to alter the sound of the whistle by placing wooden stops in it, to create a unique and distinct sound. Rail employees and family members often knew who was operating a particular locomotive by the distinct sound of the whistle. The engineer was paid $4.00 a day.

To become an engineer he had to work his way up. Quite often he started out years before as a Wiper in a yard house. Next, he worked his way up to Engine Watchman, then to Switch-engine Fireman, then Road Fireman, then Hostler, then to Engineer.

Working his way up:

Wiper

The Wiper's job was to work a 12 hour shift in the roundhouse, where he packed the internal moving parts of the engine with wads of greasy waste. The pay was $1.75 a day. This was the starting job that lead to the engineer's seat.

Engine Watchman

This man's job was to keep water in the boiler and keep enough fire going in the firebox to move the locomotive within the railroad yard.

Switch-Engine Fireman

The one learning the trade, called the Switch-engine Fireman, who worked in yard and never left on a traveling or "road" engines.

Locomotive Fireman

The fireman and engineer operated a steam locomotive as a team. The fireman managed the output of steam. His boiler had to respond to frequent changes in demand for power, as the train sped up, climbed hills, changed speeds, and stopped at stations. A skilled fireman anticipated changing demand as he fed coal to the firebox and water to the boiler. At the same time, the fireman was the “copilot” of the train who knew the signals, curves, and grade changes as well as the engineer.

Hostler

The Hostler went into the yard and picked up an engine from where the journeyman engineer left it running. He moved it into the roundhouse.

Switch-engine

Engineer

This position was held by apprentice engineers learning the trade. Their job was to move railroad cars (also known as "rolling stock") around the railroad yard. Getting loaded boxcars on the right tracks and getting them hooked up for the road engines to pick up just before leaving the station. Once the apprentice engineer proved his ability with handling the switch-engines, the next opening for a Road Engineer would be his.

Conductor

Since the 1840's, to the average nineteenth century passenger, the conductor was the most visible railroad worker they encountered. Conductors wore distinctive uniforms and hats. As train crews went, especially passenger trains, the conductor held the legal authority over the train. (They still do.)

His job required diplomatic skill when dealing with passengers. Among their duties, the conductor collected the tickets from passengers, sold passage to those who boarded the train without purchasing a ticket where there was no ticket agent, supervised the other trainmen, settled arguments, and admonished misbehaving children or inebriated passengers. A conductor often dealt with crooks and swindlers. Like first responders of today, they were required to deal with all manner of emergencies such as delivering babies or doctoring the smashed or severed fingers of one of the train's crew. He has presided over the cars in the train with a fatherly dignity. The conductor filled the public relations function for the railroad by answering passengers’ questions and helping them to resolve difficulties.

In charge of train in its entirety, there was only one conductor per train. On large trains, he might have an assistant conductor or two to handle some of the duties.

Where the engineer and fireman remained in the locomotive, Along with one or two brakemen, the conductor stayed in the caboose when he was not required elsewhere in the train. The caboose provided shelter along with a stove for heating and cooking, seats, and make-shift beds. It also included a desk and chair for the conductor. The caboose car was also a place to store shovels, brooms, wrenches, chains, couplers, lanterns, and other miscellaneous equipment.

The conductor was (and still is) the railroad employee charged with the management of either a freight or passenger train. He was the direct supervisor of the train's crew. He was required to carry an accurate watch, which was regularly inspected. He was to ensure that the train was running according to the timetable. It was the conductor who had the responsible to signal the engineer when to start moving and when and where to stop. On a freight train, the conductor was also responsible for keeping the record of the consignment notes and waybills. He directed any switching that needed to be performed in order to drop off and pick up cars along the line.

Working his way up to Conductor

A conductor typically worked his way up from Flagman.

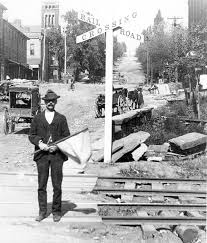

Flagman

Prior to about 1900, flagmen were called Freight Conductors. The flagman is the senior brakeman. He had worked his way up the ladder by being competent, which in many cases, meant he must avoid being killed. Since he picked new orders for the train at various stops along the way, he had to be able to read. He might also have been given the responsibility for collecting fares from passengers that rode in the inexpensive boxcars on the freight trains.

When, a train wreck occurred, or when a train was required to stop for some unusual reason, and it blocked the main set of tracks, the flagman's job was to set up warning devices along the track in the direction of any expected train. In the early days this meant they positioned themselves at a visible point as far down the tracks as possible to be able to wave a flag and warn any oncoming train of the dangers ahead.

Brakeman

During the early days of railroading, one of the most deadly jobs in America was that of Brakeman. The brakeman Inspected the train, assisted the conductor when he wanted the train to slow down or stop, operated the brakes, and assisted in switching tracks to determine the direction the train would travel. He also inspected and repaired brakes.

A brakeman's duties also included ensuring that the couplings between cars were properly set, lining up the tracks for switches, and signaling to the train operators while performing switching operations. The brakemen often rode in the caboose, the last car in the train. This allowed one brakeman to apply the brakes of the caboose quickly and easily, which helped to slow the train.

Prior to 1888 when Westinghouse developed a reliable air brake, stopping a train or a rolling car was very primitive. Iron wheels, located on top of the cars, were connected to a manual braking system by a long metal rod. Particularly in cases, such as descending a long, steep grade, the brakemen, usually two to a train, rode on top of the car. On a whistle signal from the engineer, the brakemen, one at the front of the train and one at the rear of the train, began turning the iron wheels to engage the brakes. When one car was completed, a brakeman jumped the thirty inches or so to the next car and repeated the operation. The brakemen worked toward each other until all cars had their brakes applied. On some lines, it was common practice for the brakemen to stay on top of the cars the entire time the train was in motion.

Tightening down too much could cause the rolling wheel to skid, grinding a flat spot on the wheel. When this happened, the railroad usually charged the brakeman for a new wheel. New wheels cost $45, which was exactly what a brakeman earned a month. In good weather, the brakemen enjoyed riding on top of the cars and viewing the scenery. However, they also were required to ride up there in all kinds of weather. Jumping from one car to the next at night or in freezing weather could be very dangerous, not to mention the fact that the cars usually rocked from side to side.

I do know this continued to be a dangerous job even in later years. My uncle worked as a brakeman. During a flash flood where there was hydroplaning on the tracks, he moved from car to car to apply the brakes. He was not on the roof—they had pull cords in each car to activate electric brakes by then (mid-1950s). However, as he moved through the cars, he got caught between two of them just as they jackknifed.

Keeping things coordinated

The

engineer and the conductor had the responsibility to compare watches. It was

necessary that both their watches were set to railroad standard time. Since

they shared responsibility for the safe operation of the train and application

of the rules and procedures of the railway company they also reviewed train

orders they received. To see a website showing an engineer and conductor coordinating the time on their watches, please CLICK HERE.

Along with the conductor, the engineer monitors time so the train doesn't fall behind schedule, nor leave stations early. The train's speed must be reduced when following other trains, approaching route diversions, or when regulating time over road to avoid arriving too early.

Porter

Porters made their appearance on the railroad with the Pullman cars. The first Pullman porter began working aboard the sleeper cars around 1867, and they quickly became a fixture of the company’s sought-after traveling experience. Just as all of his specially trained conductors were white, Pullman recruited only black men, many of them from the former slave states in the South, to work as porters. Mr. Pullman’s objective was to hire men who knew how to behave like the perfect servant. Their job was to carry baggage, shine shoes, set up and clean the sleeping berths, and serve passengers in the Pullman cars and at rail terminals.

My most recently published book is Kate’s Railroad Chef. The position my hero, Garland McAllister holds with the railroad at the start of the story will be covered in next month’s blog post. For the book description and link, please CLICK HERE.

Sources:

https://www.up.com/heritage/history/past-present-jobs/index.htm

https://railroad.lindahall.org/resources/what-was-what.html

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/pullman-porters

http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ne/topic/railroads/job.html

https://www.whatitmeanstobeamerican.org/artifacts/whatever-happened-to-the-little-red-caboose/

Wikipedia